Every industry that grows too fast forgets what made it valuable. Therapy is no exception.

A recent article in The Cut exposed and criticised Internal Family Systems, or IFS, a therapeutic approach that has gone from niche to mainstream in record time. I’d always thought of it as harmless, even interesting, but reading those accounts made me realise how risky it can become when taken too far.

Of course, this is nothing new. Trendy therapy modalities constantly spring up and then fade away. We’re seeing it now with “trauma-informed” everything, the psychedelic renaissance, and EMDR. But what struck me most about the IFS story, and what points to a wider theme I’ve been thinking about, is how these models spread through celebrity and influence. IFS has been championed by Gabor Maté, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Bessel Van der Kolk—figures with enormous reach and cultural authority, albeit questionable credibility.

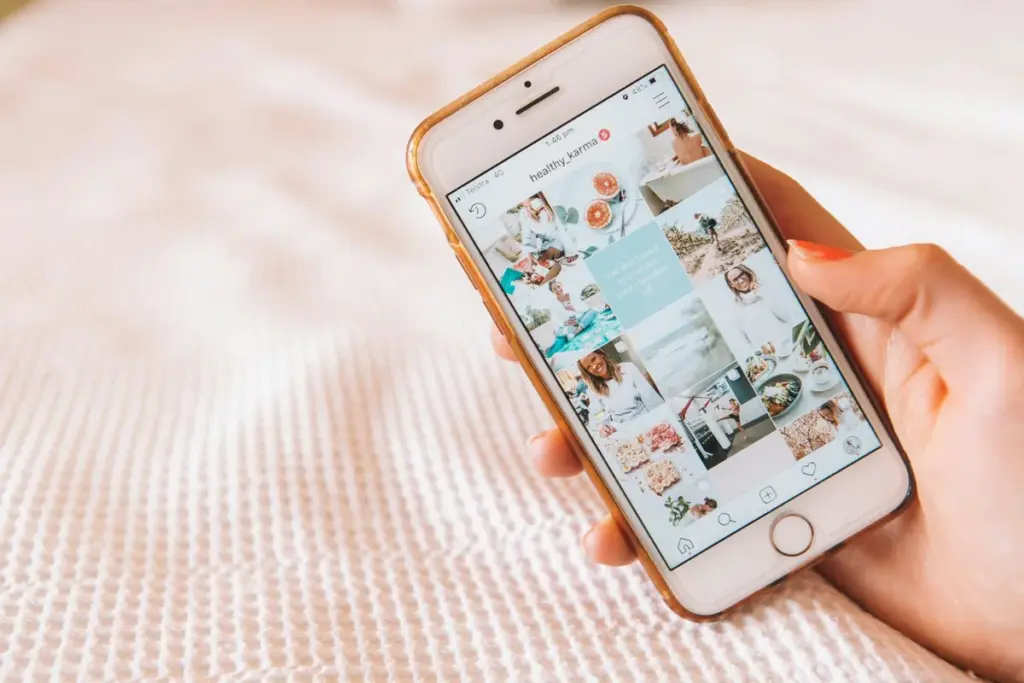

The scandal around IFS feels like a mirror of what is happening to therapy as a whole. What began as a discipline devoted to helping people work through their inner conflicts and symptoms seems to be turning into an industry of platitudes, trendy methods, polished influencers, and endless noise. Scrolling on instagram and the endless flow of therapist content, it begins to seem more like a narcissism project – a way to make money, build an image, and keep everyone feeling comfortable. It is no wonder people are increasingly confused about what therapy is, and why the wider public is beginning to question the credibility of modern psychotherapy.

The New Priesthood

We are living in the age of mental health awareness. Once fringe, therapy has become a kind of moral currency. To say “I’m in therapy” now signals self-awareness, even a “green flag” in the dating market. We confess not to priests but to clinicians and more and more we are seeking not absolution but diagnosis. There’s even a meme about “men would literally (do absurd thing) instead of going to therapy” as a way to mock men not seeking help.

When I began training, therapy was still a bit suspect, the profession of eccentrics. You found a therapist through a list of phone numbers without images, not an Instagram reel. No shiny bios, no soft lighting, no claims of superior empathy. Standards were high, training was gruelling, supervision relentless. It attempted to weed out the fragile and the narcissistic.

Now, in the boom of what sociologist Frank Furedi calls “Therapy Culture”, those same traits are often rewarded. Furedi warned twenty years ago that Western society was turning therapy into a worldview, one that pathologizes ordinary life and encourages overdiagnoses in mental health. He was right. What began as a language of care has become a kind of currency of belonging.

The new priesthood of wellness offers endless rituals: self-diagnosis quizzes, trauma reels, mindfulness challenges. The promise is salvation through self-knowledge, but only if you can afford the entry fee. A friend of mine was recently quoted between three and six thousand dollars for an ADHD assessment! He is bright, lonely, a bit eccentric. He wondered with me whether the label would make a difference to what he actually needs – friendship and meaning. In this light, the price tag feels less like care and more like a modern form of indulgence, the spiritual cost of a secular age. Here is the therapy-industrial complex at work.

The Influencer Therapist

Therapy’s public face has changed too. The clinician’s couch has become a stage. Online, the boundaries between education, branding and confession blur until all that remains is scrollable content. Therapists compete for attention in a marketplace that rewards charisma and aesthetics over depth. The result is a profession increasingly incentivized by superficialty and narcissism, the very qualities it’s supposed to help people challenge.

Influencers have also muddled what people now believe therapy is. For many, the word “therapy” no longer means a long, disciplined process of working through conflict, but a general promise of validation and self-expression. The aesthetic of therapy, soft light, soothing tones, the language of healing, has replaced its substance. Sadly, what was once a clinical relationship is now a kind of emotional lifestyle brand. The rise of therapy influencers has blurred the boundary between therapy and self-help to the point where many patients no longer know the difference.

Abigail Shrier’s “Bad Therapy” has reopened this conversation. She argues that an industry meant to heal now sustains itself by encouraging dependency and self-absorption. I don’t share all her conclusions, but her main point lands: therapy’s growth has outpaced its discernment. I believe that we are losing something deeply valuable when we allow therapy to turn emotional disclosure into social capital. It leads people, and more and more young people, to believe that endless introspection is worthy in and of itself.

They’ve begun to consume therapists like content, moving on when the feeling fades, not realising that the real work begins only in the depth of the relationship itself.

Many patients feel this. They come after seeing half a dozen therapists, starved of genuine impact, fluent in therapeutic language but hungry for something real. They’ve begun to consume therapists like content, moving on when the feeling fades, not realising that the real work begins only in the depth of the relationship itself. When a culture rewards this kind of superficialty, no wonder patients have a hard time even knowing what therapy is really about, they’ve been indoctrinated into thinking “therapist shopping” is the norm and have no idea why they are still not feeling better.

I’m constantly reminded of this basic lack of cultural education about what therapy is and how it works. Recently on a podcast I was listening to they were discussing AI therapy and how endlessly good the possibility could be for having a 24/7 therapist available. I’ve written about my own experience with AI here. It’s infuriating that this misinformation is disseminated at such scale by intelligent people (but this is a whole other article for another day).

When Help Harms

In my opinion, bad therapy is worse than no therapy. The lower the bar for entry, the greater the potential for harm. Training standards have softened (there is a debate underway that argues for doing away with therapist-in-training requirements, a move I believe is deeply alarming) and ideological fashions have hardened. In my work with patients who regretted medically transitioning, I’ve seen how well-meaning therapists, swept up in affirming rather than exploring, failed to help patients pause and understand themselves before making irreversible decisions. These are not mostly villains, just products of a system that prizes ease over discomfort and identity over integrity. It is one of the clearest examples of how therapy can become anti-therapeutic when depth is replaced by ideology.

Furedi called this the cultivation of vulnerability. I’d call it the avoidance of depth. Both describe the same drift: from the courage to think and slow down, toward the comfort of being “good” and belonging.

The Coming Correction

Markets correct themselves when bubbles burst, and therapy is a market like any other. Patients are growing sceptical of the therapy-industrial complex, the podcasts, the TikToks, the endless slogans. Some are turning to spirituality, others to community, some even to AI tools that offer endless advice and engagement. Although it pains me to admit, perhaps that, too, will serve as a kind of necessary pruning to an industry too high on its own supply.

I’ve heard patients cringe at their own usage of therapy speak in the consulting room and apologize before saying words like “trauma” or “triggered” and even within the field there’s a quiet fatigue. Many clinicians entered this work to understand the human condition, not to maintain social-media personas or chase trends. Beneath the branding, there’s still many of us longing and championing for ethics and seriousness.

A Return to Calling

The correction I hope for is not a purge but a return to substance over slogans and vocation over visibility. Therapy was never meant to be an industry. It was a calling, an apprenticeship in listening, a slow craft that demanded self-knowledge as its first principle. A supervisor once affectionately told me how as a therapist in your 50’s you can grasp what therapy really demands, in your 60’s you can practice with confidence, and in your 70’s you can become truly experienced. I long for the day when my embarrassment about telling someone I’m a therapist is due to be perceived as a strange sort of outcast, rather than what I feel today, just another feel-good cliche.

From Furedi to Shrier, the warning is the same: when vulnerability becomes virtue and self-revelation becomes status, we lose sight of the quiet discipline that makes therapy transformative. Perhaps the real task now is to rediscover that discipline, and to remember that healing is the opposite of a performance. The truth is that psychotherapy is a practice of deep comittment that still happens off-screen, between two people in a room, in anonymity. If a correction comes, it will be because depth psychotherapy still matters.

Sophie Frost is a psychodynamic psychotherapist and writer based in Berlin, offering online and in-person sessions internationally. Her work explores depth, culture and the changing landscape of therapy. Find her at The Primrose Practice.